A feeling of unhappiness or not understanding something is always what triggers me. That is where the initial research starts; it is the base. I think that because of this, fashion has always been more to me than a series of shapes, fabrics, colors and finishings. It has always been more than a product that someone could wear.

For my graduation collection at the Fashion Institute Arnhem, I stepped out of my usual personal way of dealing with, and reflecting on, the world around me. Most possibly this happened after re-reading Anne Frank: the Diary of a Young Girl. I developed a fascination with the Second World War and I was stuck in this awful Europe of some seventy years ago. The idea of using the memory of the Holocaust as the base of my collection started to be more and more inevitable. Because the more I read, the less I understood. Because after every documentary I watched, numerous new questions were raised. How could this have happened? We all know about this dark chapter in human history, but after all this time it still defies my understanding. Especially when one realises we are only one or two generations apart from it.

The fashion system is known to be fast. It is about facing forward, and selling beautiful clothes. Not the first vehicle that jumps to mind for addressing a subject as delicate as this. Fashion does not always seem to demand more of its viewer than a sense of taste and intrinsic tailoring know-how: fashion people often judge fashion solely in a fashion way. So how will the fashion audience perceive my vision? When breaking with the trend logics of fashion, and choosing to look back instead of forward – dealing with this darkest chapter in human history – I instantly felt that I would need to create some space in this tight and fast-forward facing world. And another predicament arose: how will survivors respond? I felt as if taking a risk, worried that people might interpret what I did the wrong way, and take offence in my attempt to try to understand and examine this part of our history. I had walked into memories that belong to someone else. But lastly, it is also a story about the eternally generic values of repression and freedom, and in that way still very happening and, thus, still very relevant in the here and now.

Because of this, the story that I am telling is a vital part of my work. Fabrics combined with the human body are comforting for me. I like the intimacy it brings when I realise that someone could wear it. I never chose for the scene that is unbreakably bound to these elements. This all has put me on a crossroad: I have never liked to present my work within the rigid rules of the fashion world. To show only runway photos? To see the garments on hangers on a rack? I would miss the story. Obviously it has entered each and every single garment, since I carefully chose my design principles. I disconnected sleeves from their armholes and detached parts of a pair of dress-pants from the elongated waistband, as if the lashes of whips torn them apart. I chose a lot of blacks, out of sheer respect. I used striped fabrics or printed gradient stripes on the legs of pants, referring to the uniforms of the prisoners. I sliced coats in half vertically and reconnected them with suede belts. All these things are to tell the same story; it is the grid of the garments.

And then I have to make my choices in means of presenting them. Do I push it towards fashion or art? Will I let it blend into the fashion world seamlessly or do I take a stand, and create the stage I think this story deserves? Do I diminish the story to something that has only helped me creating the shapes and finishings or do I elaborate and turn it into a socially engaged and relevant manifesto?

As always, I chose the other road; the importance of this story overrules my affinity with the fashion world. I choose to refer; to this generation, and to the one that brought us here. I refer to the designs of monuments, and to a certain passed-by film-noir. In a two-minute film made in collaboration with photographer and filmmaker Joost Vandebrug, we see a girl reminiscent of Anne Frank. She has her hair parted on the side, in a bun in a hair-net. Dark and poignant, with spots flickering on screen as if played from an old reel, we see her stamping at her own reflection, for her image is mirrored onto the floor, on her left and on her right. Later on we see that, filming her reflection in actual mirrors, she is trying to break them with her heel. Added for atmosphere we see some scenes where a kaleidoscopic view through the broken mirrors shows her glancing at us accusingly. Those familiar with the subject might see the initial reference: the Auschwitz monument in Amsterdam’s Wertheim park consists of a square of broken mirrors on the ground, with an urn underneath it. Jan Wolkers, the artist, states that "forever the sky cannot be reflected unbroken at this place".

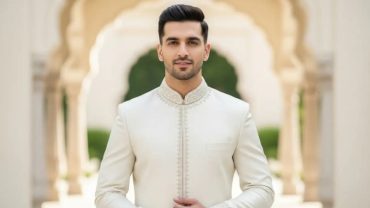

It has turned out as a film with an atmosphere reminiscent of the silver gelatin prints from the 30’s. Pleasing to the eye, and drawing instant attention, while Itzak Perlman’s violin takes the viewer unmistakably back to the Europe of the 30’s and 40’s. The actual garments, however, are barely visible. Realising that I do want to exist within the fashion world, I tried to compromise with the photos of the lookbook: I had documentary photographer Mylou Oord, who has a good know-how of the fashion world, shoot an Aryan girl with no Jewish connotation. She wears the whole collection posing in different ways. I put in small references; some shards of mirrors, some echo’s of stamping movements, and two books on the floor. Sophie’s Choice, the refined classic within literature about the postwar situation, and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close in which the Jewish author Jonathan Safran Foer merges a story about the 9/11 attacks with a story that is set in pre-war Eastern Europe. For make-up I did choose a harsh statement: a totally black lower jaw almost communicates as a piece of cloth bound around the models face, as if to silence her.

I tried my best to tell a horrible story in a way that hopefully has some beauty in it, and even while writing this I understand how very strange that must seem. I can only explain myself by stating that beauty, in this context, has mostly to do with evoking consciousness and the act of remembering, and with expressing emotion. And for that, the art of fashion seems to be the perfect vehicle.