In Renaissance times this place represented the hub of the city’s trading machine, a sophisticated production line that was said to churn out a boat a day.

The tall brick tower that still dominates the site is the place where the ships’ masts were installed as a finishing touch before they sailed out into the laguna on their missions of fortune.

This being Venice and the Renaissance, of course, the place—now part of the Arsenale where the city’s art and architecture Biennales are showcased—is as beautiful as it was once productive, having been built (between 1568 and 1573) by Jacopo Sansovino, one of Venice’s most revered architects of the period.

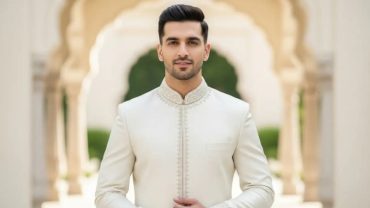

Piccioli set his snaking runway under Sansovino’s soaring arches where the ships were once sheltered to be repaired so that it appeared to float over the water. Guests were bidden to wear white.

Luckily everyone did as they were told, and the effect, as the golden light of early evening streaked the water, the stone, tile, and brick, was undeniably poetic.

To add to the spine-tingling moment, the collection was serenaded by the British singer Cosima, whose plangent voice gave a powerful twist to Calling You from the 1987 movie Bagdad Cafe, that opened the show.

It was soon clear why Piccioli had asked us all to dress in white. I am old enough to remember Yves Saint Laurent’s stately couture presentations in the 1980s, and Christian Lacroix’s frisky ones, and the frisson of excitement, astonishment, and applause that greeted their audacious color mixes, often inspired, respectively, by the women in the markets of Marrakech, or the coruscating suits of the toreadors.

Piccioli brings that same level of gasping wonder to fashion’s color wheel, setting flamingo pink, chartreuse, violet, cocoa, and mallard green ball gowns one after another, for instance.

Or he might throw a raspberry double-face balmacaan over darker pink pants and an orchid pink crepe shirt, or a lilac cashmere cape over violet pants, frog green sequin t-shirt, and pea green gloves, and then ground the look with eggplant shoes with the heft of Dr.

Martens. These last two ensembles, by the way, are part of the menswear offerings in the collection, in case you were wondering, and very persuasive they were too.

There were 84 looks in the show, and each one was a different proposition, from puffball micro-minis, (shaded with Philip Treacy’s giant trembling ostrich frond hats that moved like jellyfish), to trapeze silhouettes, skirts that hit the mid-calf or hovered above the ankle, and slinks of satin and crepe cut to spiral round the body like affectionate serpents.

From ball gown to micro mini the effect was one of commanding elegance. The fashion history sleuth will find echoes here of Madame Grès, of Cardin, and Capucci, as well as note-taking from Mr. Valentino’s own magnificent oeuvre, but Piccioli takes these iconic moments of design history and makes them uniquely and persuasively his own.

Also unique were the artist collaborations, curated by Gianluigi Ricuperati, who assembled a roster of 17 painters, including Jamie Nares, Luca Coser, Francis Offman, Andrea Respino, and Wu Rui.

Art and fashion have often united in symbiosis—think of Warhol and Sprouse, or Schiaparelli and Dali—but here the effect was a celebration of creativity, the hand, and of the nonpareil Valentino workrooms whose talented artisans evoked the source artworks through various cunning means.

There were elaborate collages of textiles, for instance, 46 in all for Look 6, Kerstin Bratsch’s The If, 2010, (as the Valentino show program notes helpfully noted, alongside the names of the craftspeople in the ateliers who have made them).

Meanwhile, the five pieces by Patricia Treib, combined in the ballgown of Look 68, called for 140 meters and 88 different textiles and took 680 hours to complete.

On close inspection, even the fine lines of Benni Bosetto’s pencil strokes (Untitled, 2020), which appeared to have been drawn directly onto the pale satin of Look 46, turned out to have been suggested by subtle hand-stitching (a stunning 880 hours of work, if you are counting).

The ball gown and cape that closed the show, Look 84, were scrolled with motifs drawn respectively from Jamie Nares’s It’s Raining in Naples, 2003 and Blues in Red, 2004, requiring 700 hours of work, 107 meters of fabric, and custom screens for the hand-printing as it had to be done on such a large scale. The effect was appropriately magisterial.

By the time the rainbow-clad models all lined the runway and Cosima was singing What the World Needs Now this editor was frankly so overwhelmed by the surfeit of beauty and emotion, and the joy of reemergence, that I am not ashamed to admit the tears sprang forth.

COLLECTION